Got 10 Minutes? Here’s One Way to Learn to Be More Curious

Recently a friend sent me a link to an article, "Test Your Focus,” which asks readers to study a painting for at least 10 uninterrupted minutes to improve focus and observation skills. I like art and I’m interested in improving my focus so I gave it a go.

I entered the site and the timer began. Instructions were simple: “In a modest attempt to sharpen your focus, we’d like you to consider looking at a single painting (Nocturne in Blue and Silver by James Abbott McNeill Whistler) for 10 minutes, uninterrupted.” The assignment stems from a Harvard art history class where Professor Jennifer Roberts requires her students to study a painting in person for three hours to better understand a piece of art. So, how hard could a 10 minute study be?

The timer on the screen started ticking and I began to study the piece of art: I zoomed in on certain areas, tried to make meaning out of the landscape, considered possible historical connections and noticed color, shades and perspective. Was that a secondary reflection of the buildings in the water? What was that small object at the bottom of the painting? Not quite sure but it looked like a cell phone and yet it couldn’t be as the painting was from the late 1800s. Yet, as I considered the painting for longer than I might have, I definitely lingered and noticed more. A small button hovered at the bottom of the screen with the words “I Quit” in case I wanted a way out.

What did I notice about my attention? I noticed that I had to work to keep myself on task and not check my phone! I got a bit wiggly. Ten minutes of uninterrupted time shouldn’t be a challenge but at first it was. I got a little bored of zooming in and out on the painting, but then I started to get more engaged. The more I settled into observation, the more curious I became. Once I was committed, my system settled down and I found space to take in more. And the choice of the words “I Quit” served as motivation to NOT quit.

I sent the link to my colleagues on Slack. I also sent it to a handful of friends who I knew might be curious about their attention. I sent it to my family. Many responded and said they’d try it, but I’m not sure how many actually stopped, clicked and observed. Did the 10 uninterrupted minutes instructions intrigue or put people off? According to the statistics at the end of the article, 25% of readers “quit” after less than 1 minute and only 25 % made it to 10 minutes or more. The other 50% fell in the middle somewhere.

Why should we care about a simple exercise such as this? Harvard Art History professor Jennifer Roberts believes we need to train students to slow down and develop patience in order to improve our observation skills (Read her article, “The Power of Patience”). She asks her students to spend what she calls, “a painfully long time” studying a single work of art in person as an effort to focus on “deceleration, patience, and immersive attention.” Roberts says, “What this exercise shows students is that just because you have looked at something doesn’t mean that you have seen it. Just because something is available instantly to vision does not mean that it is available instantly to consciousness. Or, in slightly more general terms: access is not synonymous with learning. What turns access into learning is time and strategic patience. (Italics mine)”

Why is observation, patience and, ultimately, curiosity important as a school leader? According to Gloria Mark, a professor at the University of California, Irvine, and the author of “Attention Span: A Groundbreaking Way to Restore Balance, Happiness and Productivity,” we spend less than one minute on any one screen. How does this kind of fragmented attention allow us to be our most curious, most aware and most productive selves as leaders?

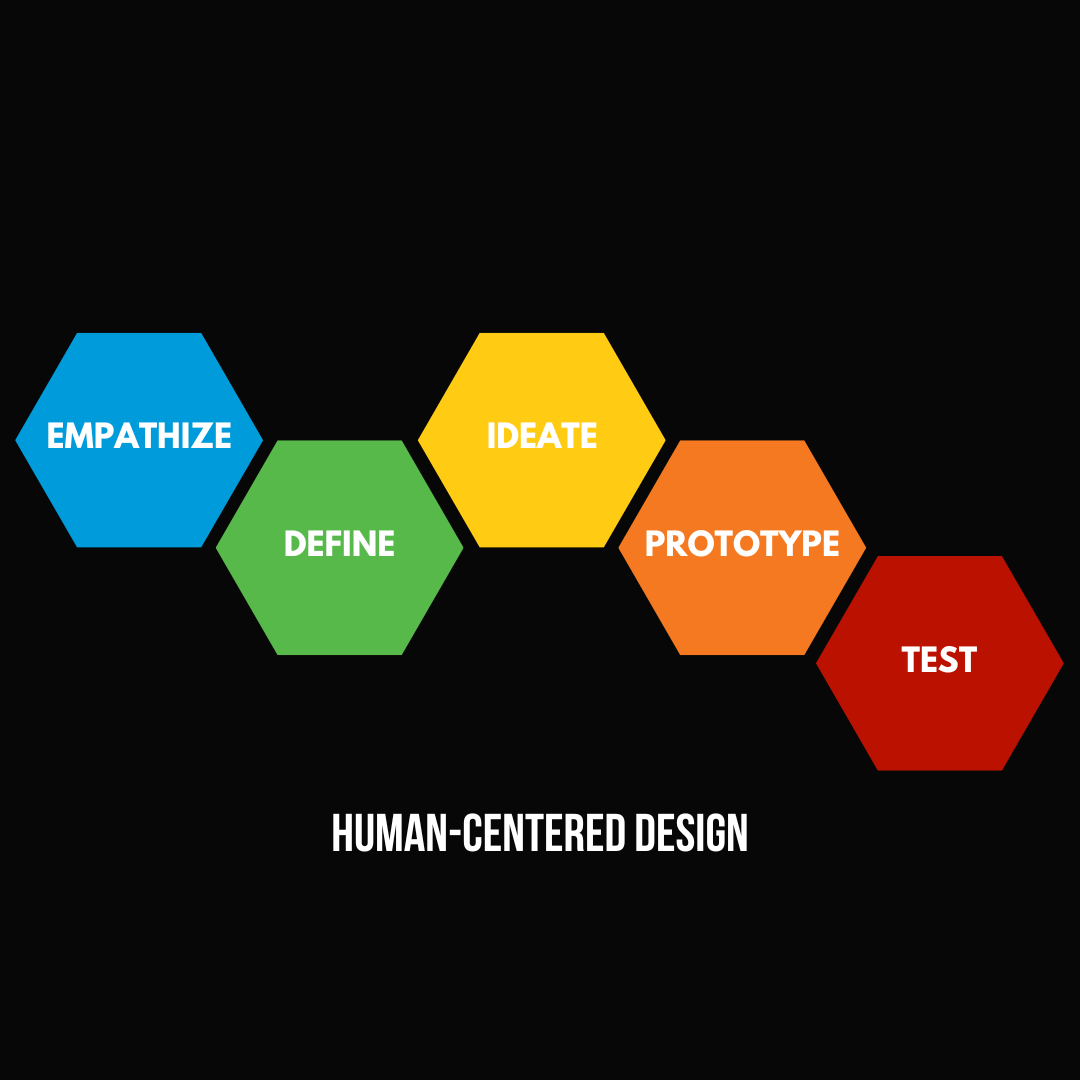

With the additional demands of school leaders’ schedules, we often start our days at full speed and end late into the evening with events, email and catch up. There is little time set aside for deep observation, and curiosity. Based on pace and urgency, we often are quick to judge and solve problems without the full consideration they deserve. One of the central tenets of human centered design is to first “just” observe to develop empathy for a situation or person before moving to prototypes and solutions.

So I asked two school leaders their thoughts on this. L+D leaders in residence, Chandani Patel (Director of DEI at Rowland Hall) and Shahana Sarkar (Dean of Academics at Head-Royce School) pondered this question. Both work in large K-12 schools where there is a lot going on all the time. Both have roles that require them to see all of the school. What might they do with designated time (even just 10 minutes) to observe and get more curious about their schools.

Chandani suggests offering students a single question and then allow them to take it in whatever directions they choose for 10 minutes (with a timer) with no adult interruption and no follow up questions. Just sit and listen. She said,” “I have learned so much by just shutting up and allowing them to be the brilliant thinkers they are.”

She suggests questions like:

What would better support your feelings of belonging?

What is something you are proud of about being a student at this school?

What is the most interesting thing you've learned this week?

Shahana, who has worked at Head-Royce for 20 years, is curious about reexamining long held systems, traditions and stories from a more neutral position in order to shed assumptions that come from being part of a community for a long time. She offers: “I’d like to look at something “old” for a longer time and allow my mind to wander. I wonder if I just sat with what we have done for years, if I might make new connections and even retrieve some long lost impressions I may have forgotten about? It’s part of being a good ancestor.”

Perhaps school leaders can use this as an opportunity to examine school artifacts and rituals through what could be termed, ‘a beginner’s mind.’ Take a fresh look at the school calendar, the lunch line, curriculum maps, all-school meetings, fundraising galas, and back to school nights? Shahana added, “As I think about long-held traditions, it makes me wonder why it was created. What is the origin story of this? Is the story holding the school back from changing it? What is still important and worth preserving? I think about students as the user, and the lens in which they are experiencing school. This is not the same one that I often use to "design" school experiences. Perhaps the act of this careful observation might better allow me to design school experiences with the students at the center.”

While it might not be realistic to spend hours studying a single school artifact or challenge, we can change our habits to strengthen our skills as observers.

What if we set aside a few minutes each week to “just” observe what is happening on our campuses without the need to judge or solve? How might it sharpen our focus and allow us to become more curious? Take the 10 minute challenge!

What if we attended a meeting without any technology (no phone, no laptop) and just brought along a notebook to draw or make notes in?

What if we created a “curiosity committee” on campus with no other objective except to observe and learn from what we see?

What if we pay closer attention to our attention to see what we might learn?

As the poet Mary Oliver said: “Pay Attention. Be Astonished. Tell About It.”